Building Customer Facing Apps That Can Handle Millions of Users Without Downtime

Most large enterprises understand that customer-facing applications are critical infrastructure. When these systems fail, the cost isn’t just technical. Revenue stops. Customer trust erodes. Operational teams scramble. And in some cases, regulatory scrutiny follows.

The challenge isn’t building an application that works for a few thousand users. The challenge is building one that remains stable, responsive, and available when millions of people depend on it simultaneously. This is where many enterprise programs encounter serious problems, often late in delivery when the cost of fixing them is highest.

Why Scale Creates Different Problems

At small scale, most architectural decisions work well enough. A monolithic application with a single database can handle thousands of users without significant issues. Performance problems can be resolved by adding more server capacity. Deployments can happen during maintenance windows. Monitoring can be basic.

At large scale, none of this holds true. Adding more capacity stops working because the architecture itself becomes the bottleneck. A single database cannot process millions of concurrent transactions. Maintenance windows become impossible because customers expect continuous availability. And basic monitoring provides no useful signal when a system serves traffic across multiple regions and handles complex failure modes.

The failure patterns also change. At small scale, failures are usually obvious. A server crashes, an API stops responding, or a database runs out of space. At large scale, failures are often subtle and cascading. A small latency increase in one service triggers timeouts in dependent services. A memory leak that would take days to cause problems at low traffic causes an outage in hours under heavy load. A configuration change that works perfectly in testing creates instability in production because the production traffic pattern is fundamentally different.

These problems are not theoretical. They happen repeatedly in enterprise programs, and they are expensive to fix after launch.

Where Enterprise Delivery Usually Breaks Down

Large enterprises typically approach these programs with either internal teams or traditional system integrators. Both models encounter predictable problems.

Internal teams often lack experience building systems at this scale. They understand the business requirements well, but they have not encountered the specific technical and operational challenges that only appear under sustained heavy load. By the time these issues surface, the architecture is already set, timelines are committed, and making structural changes becomes a political and financial problem.

Traditional system integrators bring process and governance, but they often staff programs with mid-level engineers who also lack hands-on experience at scale. The senior architects who sold the program are rarely involved in daily delivery. Technical decisions get made by people who have not personally dealt with the consequences of those decisions in production. The result is a system that meets functional requirements on paper but fails under real-world conditions.

Both models also struggle with ownership clarity. When something goes wrong in production, identifying who is responsible and who can actually fix it becomes a slow, frustrating process. In customer-facing systems serving millions of users, slow responses to production issues are not acceptable.

What Actually Matters for High-Scale Reliability

Building systems that handle millions of users without downtime requires focusing on several areas that are easy to underestimate.

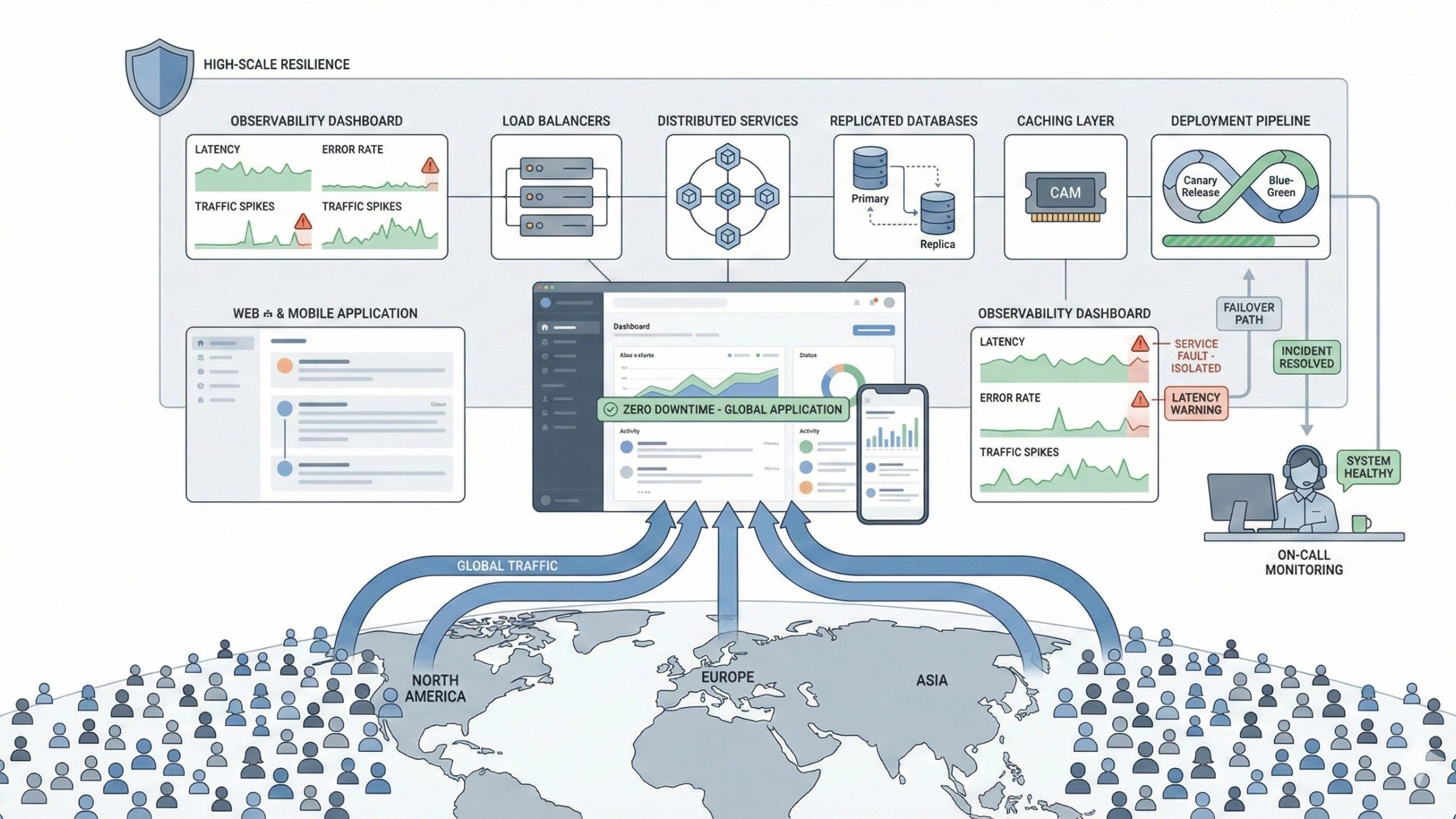

Architecture must assume failure. Individual components will fail. Network connections will drop. Dependent services will become temporarily unavailable. The system must be designed so that these failures do not cascade and do not result in user-facing outages. This requires deliberate architectural choices around service isolation, fallback mechanisms, rate limiting, and circuit breakers. These patterns are well understood, but implementing them correctly in an enterprise context with existing systems and governance constraints is difficult.

Observability must be comprehensive from day one. You cannot troubleshoot what you cannot see. High-scale systems need detailed instrumentation that shows not just whether services are running, but how they are performing under load, where latency is being introduced, and what the error rates look like across different user segments and geographies. This level of observability must be built into the system, not added later.

Data architecture becomes critical. At scale, the database is almost always the bottleneck. Designing a data layer that can handle millions of concurrent operations requires careful thinking about partitioning, replication, caching strategies, and consistency models. Enterprises often try to avoid these decisions early because they add complexity, but deferring them makes the problem worse and more expensive to solve.

Deployment and release processes must support continuous change without risk. Enterprises are used to big-bang releases with maintenance windows. Customer-facing systems at scale cannot work this way. Deployments must be automated, incremental, and reversible. Feature flags, canary releases, and blue-green deployments are not nice-to-have practices. They are required capabilities.

Load testing must be realistic. Many enterprises conduct load tests, but they test with synthetic traffic patterns that do not reflect real user behavior. Production traffic is spiky, unevenly distributed, and includes edge cases that synthetic tests miss. Realistic load testing requires understanding actual usage patterns and building test scenarios that replicate them, including failure conditions.

How Ozrit Approaches Enterprise Scale Programs

Ozrit works differently on these programs because the company structure is designed around execution rather than sales.

The senior engineers who design the architecture are the same people who remain involved throughout delivery and into production support. This is not a model where architects hand off designs to implementation teams. The people making technical decisions have personal accountability for whether those decisions work in production. This changes the quality of technical choices significantly.

Ozrit also brings direct experience building and operating high-scale systems. The team includes engineers who have worked on platforms handling millions of concurrent users at major technology companies and large enterprises. That experience shows up in architectural decisions, tooling choices, and how production incidents get handled. It also shows up in what gets prioritized during delivery. Teams with scale experience know which technical debt is acceptable and which will create serious problems later.

For large programs, Ozrit typically works with a dedicated team that includes senior engineers, platform specialists, and a technical lead who owns delivery. Team size depends on program scope, but the structure ensures clear ownership and avoids the coordination problems that slow down large system integrator teams.

Onboarding and knowledge transfer are structured to reduce risk. Ozrit does not assume enterprises have deep technical knowledge of modern cloud-native architectures or operational practices for high-scale systems. The onboarding process includes working sessions on architecture patterns, observability practices, incident response, and deployment strategies. This ensures the enterprise team understands not just what was built, but why it was built that way and how to operate it.

Timelines are realistic. A customer-facing platform designed to handle millions of users is typically a six to twelve month program depending on complexity and integration requirements. Ozrit does not compress timelines artificially to win work. Enterprises appreciate this because they have usually seen what happens when timelines are unrealistic.

Support is structured as 24/7 coverage with defined SLAs. For customer-facing systems, incidents cannot wait until business hours. Ozrit provides on-call rotations with engineers who understand the system architecture and can respond effectively to production issues.

Managing Ongoing Operations

Launching a high-scale system is one milestone. Operating it reliably over time is another.

Most enterprise programs focus heavily on delivery and underinvest in operational readiness. By the time the system launches, the team is exhausted, documentation is incomplete, and operational processes are improvised. This creates serious risk.

Effective operational management for high-scale systems requires several capabilities. Incident response processes must be defined, tested, and understood by everyone who will be on-call. Runbooks must exist for common failure scenarios. Escalation paths must be clear. Post-incident reviews must happen consistently and focus on systemic improvements rather than blame.

Capacity planning must be proactive. Customer-facing systems often experience unpredictable growth or seasonal spikes. The operational team needs visibility into usage trends, capacity headroom, and leading indicators of potential bottlenecks. This requires ongoing monitoring and regular capacity reviews.

Change management must balance speed with safety. Enterprises need to ship features and fixes continuously, but changes to production systems serving millions of users carry risk. Effective change management uses automation, progressive rollouts, and fast rollback capabilities to allow rapid iteration without creating instability.

These operational capabilities are not add-ons. They are core requirements for running customer-facing systems reliably at scale.

Why Enterprise Leaders Should Care About Technical Execution

For C-suite executives and board members, the technical details of how systems get built might seem like implementation concerns that can be delegated. But the difference between a system that works reliably at scale and one that does not has direct business impact.

Downtime on customer-facing systems damages brand reputation and customer trust in ways that are difficult to repair. Customers remember when systems fail at critical moments. They also compare enterprise systems to the consumer experiences they use daily, which set high expectations for reliability and performance.

Operational instability creates internal costs that compound over time. When systems are fragile, engineering teams spend most of their time on firefighting rather than delivering new capabilities. This slows down the entire digital roadmap and makes it harder to respond to competitive pressure or market changes.

Getting technical execution right the first time is significantly cheaper than fixing it later. Rearchitecting a system that is already in production serving millions of users is expensive, risky, and time-consuming. Making the right architectural choices before launch avoids this problem entirely.

The enterprises that succeed with large-scale customer-facing systems treat technical execution as a strategic priority, not just a delivery problem. They invest in experienced teams, they make time for proper architecture and operational readiness, and they choose partners based on execution capability rather than brand recognition or cost. That approach delivers better outcomes and lower total cost of ownership over the system lifecycle.